Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC) refers to the duration of time in which sufficient cognitive function is maintained between loss of standard oxygen levels and the onset of hypoxia.

The higher the altitude levels, the lower the Time of Useful Consciousness will be, thus reducing the response time to counteract the loss of sufficient oxygen levels.

Following the onset of hypoxia, physical and mental impairment will begin to occur prior to full incapacitation.

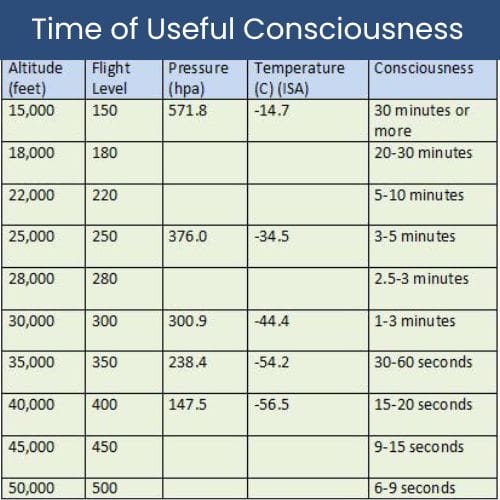

In pressurized aircraft, the TUC and subsequent required response time will range from 15 seconds to several minutes dependent on altitude.

For example, a rapid depressurization at 40,000 (FL40) would lead to a TUC of approximately 30 seconds, in which the flight crew must take action.

This action would include the donning of crew oxygen masks followed by emergency descent procedures pertinent to the aircraft type.

The paramount and crucial donning of supplemental crew oxygen in a prompt manner was highlighted in the NTSB’s report on the 1999 South Dakota Learjet 35 accident. The report can be read here.

The report’s concluding contributory factors and recommendations outline the importance of response times in relation to supplemental oxygen at pressurized altitudes.

While all certified flight crew’s health conditions must satisfy EASA Class 1 Medical Certification (Europe) or FAA Class 1 Medical Certification (United States), there are several factors influencing the TUC for each individual.

Factors Affecting Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC)

- The physical exertion of personnel at the time of loss of oxygen levels – higher levels of exertion equate to lower TUC

- Age of personnel – older personnel will generally have lower TUC

- Health Conditions of the flight crew – some health conditions can contribute to lower TUC

- Altitude in which drop in oxygen occurs – the higher the altitude depressurization occurs, the lower the TUC.

- Rate or speed of depressurization – a gradual depressurization will yield a higher TUC, a rapid depressurization will lead to a significantly less TUC.

Assessing Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC)

The FAA’s published Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC) chart highlights the calculated TUC for various altitude profiles. This chart provides awareness particularly to the TUC at higher altitude levels.

It is important to note that TUC values do not take into account explosive decompression incidents, in which TUC would be anticipated to be significantly less.

Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC) charts such as the one in the link above has been formulated following a variety of tests conducted in hypobaric chambers, in which a simulation of reduced oxygen levels at different altitudes has been reproduced.

As the factors outlined above demonstrate, the actual TUC of an individual will vary.

Importance of Knowing Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC)

As highlighted in the chart, knowing the estimated TUC time window at the respective altitude is important in relation to in-flight awareness.

Ensuring correct functioning and operation of crew supplemental oxygen prior to flight is integral to any pre-flight phase.

The 15-30 second TUC window estimated at the higher altitudes (FL30+) requires flight crew to have sufficient levels of awareness during flight.

Modern commercial aircraft are equipped with aural and visual alerts which provide indications in relation to a rise in cabin altitude. In Boeing aircraft, this is provided by an Altitude Horn system, which provides a persistent aural alert.

In relation to human factors, TUC highlights the importance of proper fatigue management within flight crews, particularly during longer sectors.

When managing fatigue levels, it is important to recognize the potential for reduced response times of individuals in instances where fatigue is high.

Read More:

Cabin Altitude and Aircraft Altitude – Aircraft Pressurization

Airport Mapping Database (AMDB) – Functions and Features

After visiting more than 60 countries, I have probably been on every type of plane there is and visited countless airports. I did my very first international solo trip to South Africa at the age of only 16 and haven’t really stopped traveling since.

Despite the adventurous travel itch, I do have a nerdy side as well – which is satisfied by writing about all things aviation “too boring” for my regular travel blog.